Period poverty is a global issue where financial constraints prevent girls and women of any age from accessing sanitary products for their periods.

Without access to sanitary products, girls and women are forced to improvise or not use any sanitary products at all.

Rags, toilet roll, paper towels or torn clothes could all be used as substitutes and may be used for longer than is healthy. Menstrual stigma and lack of education create a cruel self-perpetuating cycle that prevents women and girls from seeking help.

Period poverty does not only encapsulate access to sanitary products, but also access to lockable, safe toilets, hand washing facilities and hygienic waste disposal provisions.

Period poverty is not just a deeply ingrained socioeconomic issue but also a public health crisis.

It’s indicative of how menstrual education is still severely lacking across the world, even now in the 21st century.

Table of Contents

How Common is Period Poverty?

Period poverty is alarmingly common and occurs everywhere, in every country, and whilst it is generally true that poorer countries share the worst of the burden, it’s shockingly widespread.

Globally, half a billion women and girls live in period poverty each month. According to UNICEF, over 2.3 billion women don’t have access to basic sanitation services, which exacerbates the problem, and just 27% have access to basic handwashing facilities at home.

The problem intensifies for disabled girls and women, or those who are living through war and conflict, humanitarian crises or natural disasters.

In India, only 42% of women and girls have access to period pads and many are totally unaware of what to do when they first experience their period. In Africa, UNESCO found that girls may miss up to some 20% of their school year due to menstruation, with many dropping out of school altogether when they have their first period.

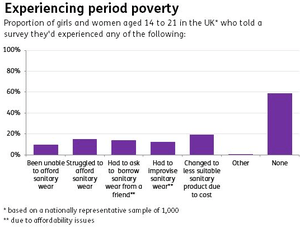

In the UK, Plan International found that 1 in 10 girls aged between 14 – 21 has been unable to afford sanitary products. 1 in 7 had found it difficult to afford sanitary products and had improvised sanitary wear or had to ask friends to borrow products.

In the US, 1 in 5 girls were found to have missed school at some point due to lack of sanitary products. It’s the same in the UK; studies amongst school children in deprived areas reveal that more girls are missing school when they’re on their periods due to insufficient sanitary products.

ITV revealed that sanitary products are now included in foodbank deliveries as councillors and charity workers become increasingly aware families that are unable to afford them themselves.

“Sadly there are many cases where vulnerable children and families don’t even have access to buy pads, because for them it’s a choice of do I buy nappies for my child or do I buy pads?” – Rajveer Kaur, teacher in Leeds.

Period poverty’s self-perpetuating cycle of stigma has been linked to domestic abuse, persecution and discrimination amongst women. It is very much a human rights issue as well as a public health issue and goes right to the very heart of questions surrounding women’s fundamental needs, their rights, and society’s duty of care unto them.

Period Poverty Isn’t Just About Sanitary Products

Period poverty does not just cover access to sanitary products themselves, and the barriers to affordability, but also access to hygienic lockable toilets and access to hygienic waste disposal methods. Lack of access to safe running water and handwashing facilities also results in poorer menstrual health for those who are affected by period poverty.

Research by charity Women Across Frontiers has found that doors in Ugandan schools lack locks and are insecure, and that only a small percentage of schools have safe running water in toilets. This is emulated in many other countries, not just across Central and South America, Asia and Africa, but also in Europe. For example, in India, there are an estimated 63 million adolescent girls living without a toilet and safe sanitation, including fresh running water, within their own homes.

Public health studies in the UK have also highlighted safe locking doors and handwashing facilities as being imperative to good menstrual hygiene management (MHM).

Charity initiatives tackling period poverty are not just looking at access to sanitary products, but also to how we can better accommodate girls and women who are menstruating in public places, providing them with safe and secure facilities to manage their menstrual hygiene.

Period Poverty as a Public Health Risk

Period poverty has many impacts on both the mental and physical health of sufferers and is a public health risk.

In India, it is estimated that some 70% of reproductive diseases amongst girls and women are caused by poor menstrual health. In some African countries such as Kenya, women may even use soil and mud to prevent menstrual blood from leaking.

Mental Health

In terms of mental health, poor access to proper sanitary products can cause social isolation, stress, anxiety and depression. The stigma attached to seeking help often means that girls and women suffer alone.

A UK public health study found that women who suffer from period poverty can develop coping strategies and tend to eat less. A North American survey of 1,000 girls who suffered from period poverty found that some 39% reported experiencing anxiety and depression.

This is only intensified when girls and women have to miss school or work whilst they’re on their period, with evidence suggesting girls cannot focus on their studies when they are experiencing anxiety resulting from their period. Some of these mental health effects go some way in explaining why the dropout rates for girls in many countries are much higher than for boys.

In June 2020, a BBC report found that charities across the UK were responding to a massive rise in demand for sanitary products following the worsening of period poverty over the coronavirus pandemic. Charity workers reported that depression amongst girls, women, and their families had really worsened surrounding poorer access to sanitary products, largely because schools, community centres and charities had been forced to shut down.

Physical Health

The physical health impacts of period poverty have been researched through menstrual hygiene management (MHM). Poor MHM has been linked with heightened risks of urinary tract infections and bacterial vaginosis. In serious cases, infections caused by the use of ineffective or unhygienic sanitary wear such as rags, can lead to sepsis, which can be fatal.

One study in Uganda found that 90% of 205 girls aged between 10 – 19 failed to meet standards for MHM, vastly increasing their risk of infection and other complications. A similar study in India found that poor menstrual hygiene and the use of unhygienic pads combined with lack of access to running water or handwashing facilities could increase infection risk.

It’s clear from these studies that period poverty does not just relate to sanitary products themselves but also to the facilities that support menstruating women. Many of these issues go hand-in-hand with poor sanitation and lack of clean running water, etc.

The Causes of Period Poverty

To analyse the causes of period poverty today, we have to take a brief look at the history of menstruation.

A Brief History of Menstruation and Menstrual Taboos

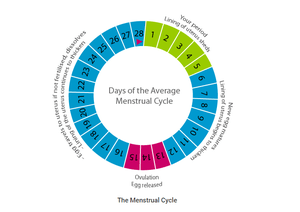

In 28-day cycles on average, hormones in the female body begin the process of menstruation. The uterus, or womb, prepares a thicker lining in preparation for a fertilised egg.

Once that egg is released and goes unfertilised, the uterus sheds this lining as it no longer needs it, and it’s released through the vagina.

Females menstruated before we even evolved into homo sapiens, or modern humans. All archaic species of humans menstruated, and female Great Apes such as gibbons, chimpanzees and gorillas also menstruate.

Many other mammals have oestrous cycles, but don’t actually menstruate. This means that most of the hormonal processes that trigger menstruation are similar to as they are in humans, but that the lining of the uterus is generally reabsorbed into the body rather than released through the vagina.

The evolutionary causes of menstruation are complex and still much-debated. A broad consensus suggests that menstruation is an energy-saving exercise. Maintaining a thick uterus requires considerable energy and that’s tough on the body, so the body evolved to cycle between a fertile state with thicker uterus walls and a less fertile state.

Menstruation could have also evolved as a need for human embryos to have thicker, deeper uterus walls for the protective and nurturing effects.

In any case and under any definition, menstruation is an entirely natural process, and it’s clever, complex, and supports and facilitates new human life.

Ancient Cultures and Menstruation

Our knowledge of menstruation in ancient history is limited, but we do know that humans lived shorter lives and thus, menopause also occurred earlier.

The Greek philosopher Aristotle provides one of the earliest records of menstruation and menopause, and he noted that women in Ancient Greece tended to stop childbearing at younger ages and went through menopause at 40 or earlier.

Menstruation was also seen as synchronous to the moon cycle as period cycles take place across 28-day cycles on average, similar to the lunar cycle. Many ancient cultures such as the aborigines in Australia and tribes in Central and Southern America thought that menstruation was tied to the lunar cycle, a symbol of stability and spiritual power.

Darwin was one influential scholar that thought period cycles could sync to the moon due to the connection between ancient society and the lunar cycle, but modern-day studies have found little or no correlation – scientists believe this is likely a coincidence.

Menstruation was symbolically and spiritually powerful in other cultures and societies too; Pliny the Elder in Ancient Rome wrote that a menstruating woman can scare off hail storms or encourage the growth of healthy crops. But, he also hinted at the negative magical consequences of menstruation.

The Cherokee saw menstrual blood as a sign of feminine strength that had the symbolic power to destroy enemies.

Menstrual blood also played a crucial role in Mayan and African magic, where the Maya moon goddess is reborn from the blood of a menstruating woman.

The point is, menstruation was respected by many ancient cultures who saw it as the wonderful thing that it actually is.

So, when did this change?

Menstruation through the Middle Ages

Menstruation began to take a different course through the middle ages.

Many anthropologists point out that menstrual discrimination was often linked to religious teaching throughout the middle ages, but it’s a complex web to disentangle.

Menstrual taboos took root before modern religion. The magically enshrined ancient beliefs about menstruation often hung in an awkward balance with other beliefs surrounding period blood’s dark magical powers.

Menstrual blood was an ingredient of black magic spells in Africa and the Americas and these ideas came to influence taboo around the subject of menstruation.

Anthropologists have put forward a variety of other factors for menstrual taboos, including male jealousy of a woman’s archetypal role in the formation of new human life and misconceptions about blood as a whole, including how blood is often seen as a sign of death, pain and sorrow.

Others suggest that menstrual taboo could have been formed from a selfish patriarchal move by men to marginalise women who were not sexually available. Organised religion helped reinforce menstrual misconceptions, mixing up menstrual blood with blood’s negative imagery in religious teachings.

Throughout this time, it was the task of women and women alone to deal with menstruation, and there was little obligation on society to assist them.

Commercial period products only began to surface in the late 1800s which is when some clinicians realised that bleeding through one’s clothes was likely unsanitary.

Even then, the tone surrounding menstruation was starkly unhelpful and unaccommodating to women.

Earlier ideas surrounding menstruation’s mystical or magical power had all but dissolved – periods were now a commercial problem that needed to be fixed.

Menstrual Taboo is Alive and Well Today

Despite a mixed and complex history, it’s fair to say that menstrual taboos have become deeply ingrained within most societies around the world.

Menstruation wasn’t even discussed on terrestrial American TV until 1985!

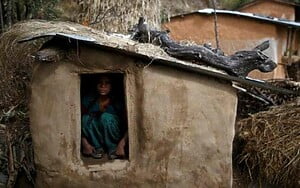

Perhaps one of the most visceral forms of modern menstrual taboo is chhaupadi, an ancient Nepalese tradition where girls and women are banished from homes to menstruate alone in mud huts for the duration of their period. It is now illegal in Nepal but is still widely practised – there are similar forms of chhaupadi practised across other Asian and African countries.

On the whole, modern education has failed to put forward the message that period blood is the same as any other blood and that menstruation is entirely natural, tolerable – a hallmark of human life’s miraculous and continuous quest for survival. In some cultures, the ideas surrounding menstruation’s dark magical powers still persist today.

In reality, menstrual blood comes from a complex organ in the body that is so clean, so hygienic, that it can support the development and birth of a baby.

Not only is this organ and reproductive mechanism a triumph and wonder of evolution, but really, it should quite simply pose no practical problem to the life of any girl or woman.

And what really is a bit of blood? Blood keeps us alive; it’s natural, healthy.

There is no reason why menstrual blood shouldn’t come under the same bracket as any blood; as a natural activity, a natural component of what it is to be human, and what it is to be a female.

Lack of Education and Period Poverty

Turning our attention to the here and now, what role does the lack of menstrual education play in period poverty itself?

Today, it really depends on the culture surrounding menstruation in different countries and societies.

Sanitary Product Marketing

The marketing strategies that surround modern sanitary products have often reinforced the view that women need to shield menstruation from society. The message is that women should tackle the periods alone, in their own time and space without support and assistance from others, particularly men.

The Western or ‘developed’ route to menstrual education has seen menstruation become part of the biology curriculum.

Whilst this is undoubtedly the right path of direction, the marketing surrounding sanitary products remains pretty one-dimensional.

On one hand, biology teaches us that menstruation is an intrinsic component of the female body and its anatomy, an important and complex evolutionary mechanism that supports the formation of human life.

On the other hand, sanitary products are still mass-marketed as a commodity, a mod-con, or convenience product, that are separated by their performance and features. More expensive products are supposed to grant special benefits and greater protection for women.

Commentators note that whilst advertising and marketing surrounding sanitary products have evolved and become more broadly feminist and empowering, there is still an undercurrent of fear of ‘discovery’, with products being marketed as especially discrete, easy to apply and manage in a hurry or in private without anyone knowing, perhaps for fear of embarrassment.

This could be indicative of our basic intuition surrounding a private and sensitive part of our bodies, that we want to look after menstruation in a way that is private and personal to us – that women don’t want to involve others in menstruation, and that this is pro-choice.

But also, some remain sceptical of how modern sanitary product marketing still heavily revolves around its commercial viability. For women to part with their cash for sanitary products, marketers sell them a motive – that motive plays into the narrative of menstruation being a lonely ‘task’ that needs to be ‘deal with’ without ‘discovery’.

Some ad campaigns have tried to digress from these typical depictions of women shielding their periods from ‘discovery’. One Australian ad campaign showed menstrual blood on a period pad in an advert and was met with fierce criticism including 600 official complaints with viewers citing that it was ‘horrible’ and ‘disgusting’ to show actual blood in relation to menstruation.

Marketing guides produced for top brands show companies how to market what they say is a ‘socially awkward’ product.

In 2020, the New York City’s Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA) refused to run ads for a women’s underwear brand that were marketing underwear for menstruating women by depicting a halved grapefruit resembling a vagina.

There are reasons to take heart, as some of these ad campaigns fought back and were embraced by communities of women who saw the virtue in their light-hearted, frank and refreshing, non-conventional approach.

But still, clearly, there is a persistent undertone here, one that reinforces menstrual taboo and stigma.

Menstrual Education Throughout the World

In many ways, we have the luxury of arguing over whether or not a billboard is offensive or not. Women and girls in other countries are dealing with much worse manifestations of poor menstrual education.

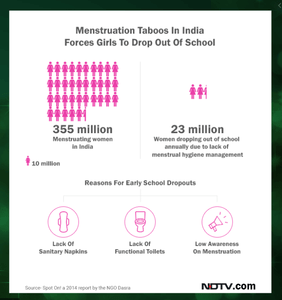

India provides a prolific example where 71% of girls do not have any knowledge of what menstruation is until their first period. Menstruating women and girls are shamed, often aggressively, and can be excluded from family dining, work and other activities whilst they’re on their periods. The lack of education extends to school too, where menstruating girls tend to take 6 days off a month for menstruation through shame and fear of discovery.

The school drop-out rate of girls is 23%, considerably higher than boys, and menstrual shame is thought to be a leading factor.

Again, marketing sanitary products as a modern convenience ‘mod-con’ product rather than a necessity adds to the problem. Sanitary products in India cost 300 rupees ($4.50) a month, which can be equivalent to several days’ wages.

In Africa, many of the same statistics surrounding school drop-out rates are mirrored and women might miss as many as 50 days of work a year due to menstruation. Poor menstrual health has been observed across many African countries and access to sanitary products is very low with over half of women improvising sanitary products each month.

Improvising pads from clothes or rags tied around the legs are common and many of these are found to be unmaintained or not replaced for the duration of menstruation.

One report by the education charity Coco suggests that girls are found to be incredibly unlikely to ask their families for assistance with menstruation, particularly their fathers for fear of sexual abuse. Through a lack of education, girls generally had little idea of the risks of poor menstrual health.

Menstrual education here lies at the intersection of both cultural attitudes towards menstruation and the attitudes of women, girls, and men. Anthropologists here tend to agree that men are the driving force of stigma which is often enforced through religious practice and that women have little opportunity to engage in open dialogues about menstruation, even with their friends or mothers. For the women themselves, lack of education makes the process of menstruation much riskier for their physical health through the use of unclean, improvised sanitary products.

The Cost of Sanitary Products

The cost of sanitary products, limited access and education/awareness all contribute to period poverty.

Cost and access are pivotal issues and pose the greatest physical barriers between women and menstrual sanitation and hygiene.

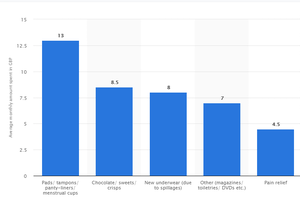

In the UK, women spend £13 a month on average on period-related products and other costs related to menstruation. One of the greatest farces surrounding the cost of sanitary products is that they have been taxed with VAT like alcohol, sweets, electronics and most other ‘non-essential’ commercial products.

‘Tampon tax’, a 5% VAT levy on all sanitary products in the UK, will be finally lifted by 2021, marking the success of some 20 years of activism from women’s rights groups.

Period poverty is still set to increase in the UK though with sanitary products being added to food bank deliveries.

NGOs that work to alleviate period poverty in Africa, Asia and South America have had to turn their attention to towns and cities throughout the UK where teachers and social workers are reporting increasing incidences of period poverty throughout schools.

Disposable Sanitary Products vs Reusable Sanitary Products

Disposable sanitary products are a dominant force in the sanitary product market – the most popular choice worldwide. They keep women buying pads, which keeps the money flowing to brands. The average woman may go through some 10,000 or more disposable pads in her life on an average of 22 items per cycle.

Many women simply aren’t aware that there is a solution – reusable products.

Haven’t considered sanitary products? The main brands don’t push them as they make a killing from disposables.

Reusable sanitary products like reusable pads yield many benefits and they’re totally hygienic and very comfortable. A woman may go through 22 disposable pads a month, but reusable pads can last over 5 years!

You need around 12 – 15 reusable pads per cycle (when taking into account washing), and these can last many years if you look after them properly.

The rising popularity of reusable pads is helping women take the power back from the main brands that extort their periods.

Trade to Aid advocates for the use of reusable pads which are more environmentally friendly than disposable pads, more ethical and reduce demand on the commercial disposable pad market.

They’re also super-comfy and don’t contain harmful chemicals.

Progress Has Been Made

The cost of sanitary products has been under intense pressure and finally, progress is being made.

Scotland is set to become the first country in the world to place a legal obligation on councils to provide free sanitary products to those in need.

Similar movements are becoming more common throughout Africa, for example, girls in some parts of Kenya can ask for free sanitary pads and a 15% tax on sanitary products was removed by the South African government back in 2019.

The continuous hard work of NGOs has helped improve access to sanitary products in areas where they simply weren’t an option before, but nonetheless, period poverty is set to continue and grow if programs don’t remain in place continually.

The Way Forward

Persistent activism from women’s rights groups around the world has begun to catalyse change.

Repealing taxes on sanitary products has been a major first step:

- India repealed a 12% sanitary product tax in 2018 after months of campaigning

- South Africa similarly repealed a 15% tax on sanitary products in 2019

- The 5% sanitary product tax in the UK was scrapped in 2020

Of course, the price of sanitary products remains unaffordable in many places around the world and as we’ve learnt, period poverty is not just about cost.

But, this shows that activism does make a difference – that is one way we can tackle period poverty.

The Role of Charities

Period poverty has been the focus of hundreds of charities that are spread throughout the world. The first step is to ensure that the poorest and most vulnerable members of society have access to sanitary products and know how to use them properly. Stopping women from using mud, soil, and dirty rags, etc, is a critical priority as this can cause serious health complications or even death.

Whilst any sanitary product is better than this, reusable products such as reusable pads are amongst the most promising tools to help lift the poorest out of period poverty. They cost less in the long-term and help normalise menstruation amongst both women and men.

Education plays a key role here and involves both boys, girls, men and women. Changing male attitudes towards menstruation is critical in countries where menstruating women are shunned, discriminated or persecuted. Some governments have taken action, e.g. in Nepal, the practice of chhaupadi was banned in 2005 and stronger penalties were rolled out in 2017, including a 3-month jail sentence – it seems obvious that this is not enough for that level of abuse.

Education efforts need to continue to establish that menstruation is entirely natural and should be shame-free – it is an essential component of our biology that deserves respect.

Your Role

Whether you are a woman or a man, you can play a role in ending period poverty.

Women, your consumer choices really matter.

By moving away from disposable commercial products, you can help end the commercialisation of menstruation.

Reusable pads are an excellent tool in the march against period poverty, and they’re ethical in other ways too.

Men, your attitudes also help shape the narrative around menstruation.

Period poverty is a complex and systemic problem, and no demographic is to blame. But, menstruation needs to be appreciated as what it is. It is a remarkable and essential biological process that helps support life, and one that women should be able to control how they like, free from shame and constraint.

Menstruation is one of the reasons why we are here right now – we need to learn to respect that.